An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.  An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know. Unit:

American Red Cross, attached to the 35th Infantry Regiment

Date of Birth:

July 16, 1912

Hometown:

Holyoke, Massachusetts

Date of Death:

April 11, 1945

Place of Death:

Balete Pass, Philippines

Awards:

Silver Star

Cemetery:

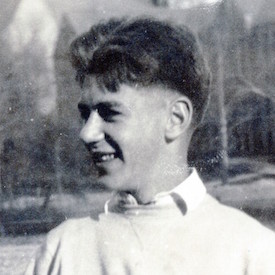

George Allingham was raised a devout Catholic. He and his brother, David, served as altar boys in their youth. His father lived in Hartford, Connecticut.

After attending Fordham Preparatory School in New York City, he graduated from the University of Notre Dame in 1933. In 1938, he received his master’s degree from Columbia University Teacher’s College. The same year, he married Blanche Martin, and they resided on East 53rd Street in New York City.

Allingham served as Chair of the Department of Speech and Drama at Fordham University and was an instructor at the College of the City of New York. His profession was as a teacher, but his passion was the theater. He worked with the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in the Federal Theatre Project, the first and only federally sponsored and subsidized theater program from 1935 to 1939. One of his final performances was at Columbia University. He starred in Witch Hunt, a play written by a Columbia University graduate, which opened on October 13, 1941.

In 1943, Allingham joined the American Red Cross and was appointed Field Director and assigned to the 35th Infantry Regiment stationed in Manila, Philippines. To be accepted by the Red Cross during World War II, applicants generally needed to be college graduates and be in good physical condition. Allingham acted as a liaison between service members and their families back home. Among his other duties he organized blood drives (called blood services at the time), attended to health and safety concerns, and completed basic clerical tasks.

As was the case with most Red Cross field directors, Allingham pitched his tent close to those whom he served. He prioritized his day’s work and supervised his assistants in order to accomplish tasks to protect life and health of all those with whom he came in contact.

The American Red Cross also provided Camp Services, which required Allingham to conduct counseling and guidance for service members. He provided a means of communication between families back home and the armed forces on the front line. He secured reports on family conditions and provided financial assistance through Red Cross loans and government grants to meet emergency needs for service members and their families.

Allingham directed American Red Cross volunteers who worked in Service Clubs often found in hotels of major cities or in small facilities in towns and villages in theaters of war. The large clubs offered not only meals and recreational activities but also overnight accommodations and such amenities as barber shops and laundries. The Red Cross also operated rest homes in usually rural and tranquil locations overseas for service personnel needing respite from the pressures of war. The homes provided sleeping accommodations, meals, and a variety of recreational pursuits for service members who were assigned there by military authorities.

Furthermore, the American Red Cross formed councils that met emergency and supplemental needs for equipment, supplies, and services for U.S. Army and Navy installations by coordinating the resources of local communities. Military authorities made emergency needs known to field directors, such as Allingham, who called on local Red Cross Councils for help. Councils provided a wide range of items from garden implements to musical instruments, as well as furniture, books, magazines, and newspapers. They also arranged ward parties, held art exhibits, and booked movie and theatrical presentations.

In April 1945, as one of his many duties, Allingham drove an ambulance on the Balete Pass, an area approximately 150 miles north of Manila. This particular duty brought him to the battlefield and the men he served. His ambulance was struck by mortar fire; he died of a fatal wound to the head.

These courageous actions qualified George Allingham for the the Silver Star, the third highest U.S. combat-only award for acts of valor and gallantry in action in support of combat missions of the United States military. It was awarded to Allingham on the recommendation of the Commanding Officer of the 35th Infantry Regiment.

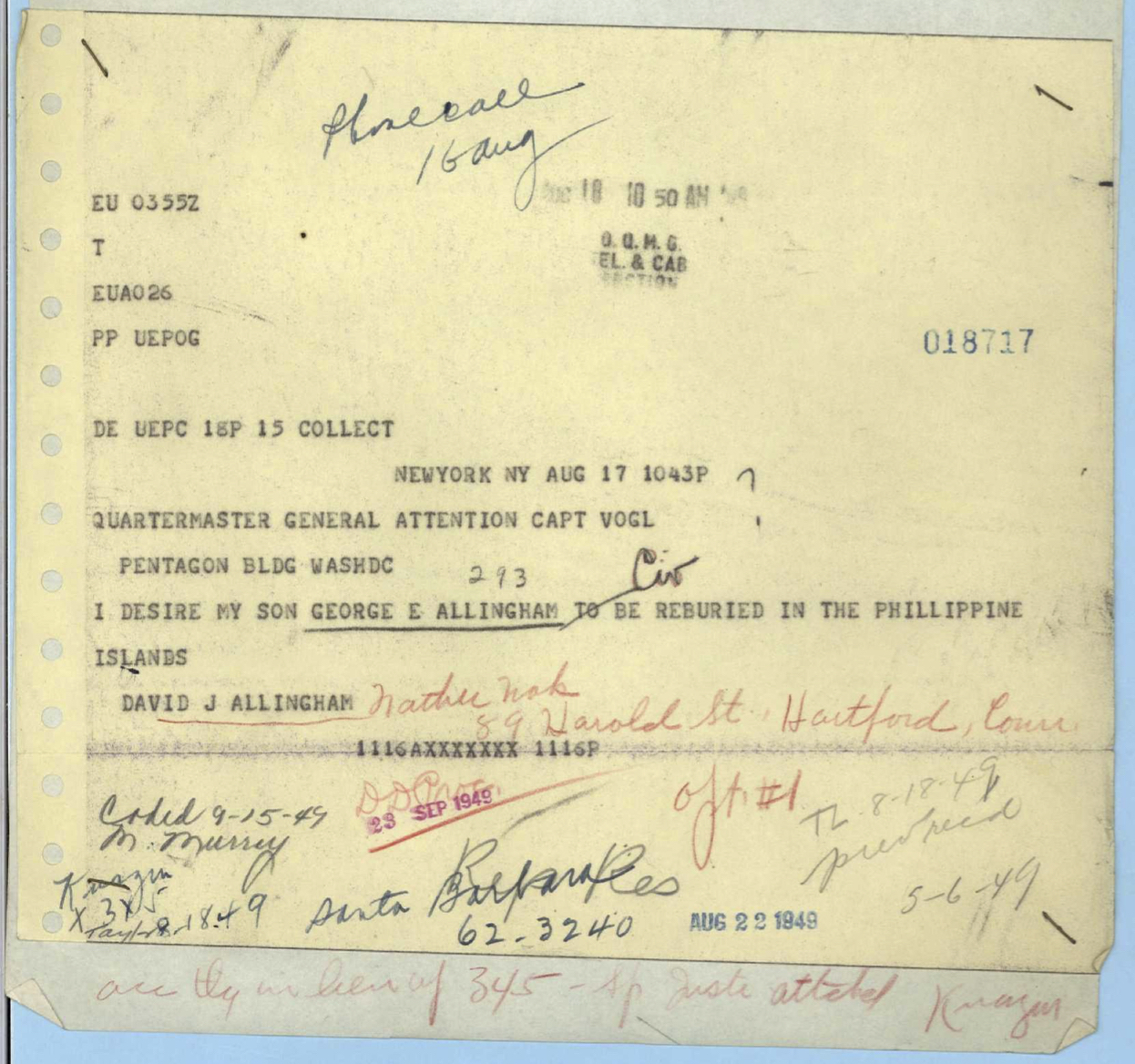

Ultimately his father, David, made the decision to bury his son’s remains in the Philippines. At the request of George’s brother, David, the American Graves Registration Service notified his father and widow when his remains were transferred. On October 18, 1949, his remains were laid to rest in Manila American Cemetery. George Allingham will always be remembered for his acts of selfless valor.

Allingham Family Photographs. 1920s-1940s. Courtesy of George Allingham.

Armstrong, James E. ed. “For God, Country, and Notre Dame.” The Notre Dame Alumnus 23, No. 3 (1945): 13. www.archives.nd.edu/Alumnus/VOL_0023/VOL_0023_ISSUE_0003.pdf

Exterior view of “Club 22,” the American Red Cross canteen at the 22nd Replacement Depot, Manila, Luzon, Philippine Islands. Photograph. August 20, 1945. National Archives and Records Administration (A30609). Image.

Federal Theatre Project Photographs, Collection #C0205, Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries. scrc.gmu.edu/finding_aids/ftpphoto.html#

“George E. Allingham.” American Battle Monuments Commission. Accessed October 1, 2016. abmc.gov/node/550721#.WbvCg8iGPIU.

George E. Allingham, Individual Deceased Personnel File, Department of the Army.

Korson, George. At His Side: the Story of the American Red Cross Overseas in World War II. New York: Coward-McCann, 1945.

“Warburton Theater Presents Barry Play.” Bronxville Review 35, No. 39 (1936): 8.

news.hrvh.org/veridian/cgi-bin/senylrc?a=d&d=bronxrev19361002.1.8#

Watkins, Marcella. Telephone interview with the author. October 2016.

“World War II and the American Red Cross.” American Red Cross. Accessed September 1, 2017. embed.widencdn.net/pdf/plus/americanredcross/ywdnimnrvz/history-wwii.pdf?u=0aormr.

This profile was researched and created with the Understanding Sacrifice program, sponsored by the American Battle Monuments Commission.

The American Battle Monuments Commission operates and maintains 26 cemeteries and 31 federal memorials, monuments and commemorative plaques in 17 countries throughout the world, including the United States.

Since March 4, 1923, the ABMC’s sacred mission remains to honor the service, achievements, and sacrifice of more than 200,000 U.S. service members buried and memorialized at our sites.

Invalid input. Please use only letters, numbers, apostrophes, hyphens, or periods.